What we know and what we need to know more about

Mohamed Aden Hassan, Sahra Ahmed Koshin, Peter Albrecht, Mark Bradbury, Fatima Dahir Mohamed, Abdirahman Edle Ali, Karuti Kanyinga, Nauja Kleist, George Michuki, Ahmed Musa, Jethro Norman & Obadia Okinda

A man checks the network reception on his phone in the village of Faleyare in Northern Somalia. Photo: IRCR/S.N., 10/10/2019, reference: V-P-SO-E-00932

Diaspora humanitarianism is characterised by rapid mobilisation and engagement that is built upon social networks, affective motivations, informal delivery and accountability mechanisms. This has implications for how it fits into the broader international humanitarian system.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

■ Diaspora humanitarianism grows out of transnational connections that link diaspora groups with their families and homelands. This relational and affective dimension enables rapid mobilisation and delivery to hard-to-reach areas.

■ Remittances to conflict-affected countries

surpass official humanitarian aid six times, blurring boundaries between short-term emergency relief and long-term development.

■ Accountability practices tend to be informal and trust-based, structured around reputation. Overall coordination with formal political or humanitarian systems is usually absent.

In 2020, the World Food Programme (WFP) received the Nobel Peace Prize for its efforts “to prevent the use of hunger as a weapon of war and conflict.” The WFP has a clear identity as a global brand, with codified working procedures that are easily recognisable, seemingly transparent and manageable. Yet, like many international humanitarian organisations, it can be slow to mobilise support during emergencies.

In contrast to established international bodies, there are a host of so-called new humanitarian actors that are characterised by rapid mobilisation and greater flexibility. Some of these target small communities areas, and indeed, sometimes individual family members.

Among these actors is the diaspora – a heterogenous category of globally dispersed migrants, displaced persons and their descendants that individually or in groups mobilize to channel support to their (ancestral) homeland(s) in the aftermath of disasters.

Ranging from projects organised by NGOs, to smaller community groups and ad hoc individual assistance, diaspora humanitarianism forms part of the wider patterns of transnational practices that link diaspora groups with their families and homelands. Such practices support everyday life, development projects, or relief measures in disaster situations alike, indicating that diaspora humanitarian assistance may serve several purposes.

The affective dimension of diaspora humanitarianism is commonly considered a challenge to the principles of impartiality and neutrality associated with the established humanitarian system. Hence, diaspora humanitarian actors are often overlooked by international organisations. At best, their relationship is ambivalent, with neither party fully comprehending nor accepting the role of the other. Below are four key propositions relating to diaspora groups and their role as humanitarian actors, for policy makers, practitioners, and researchers to consider.

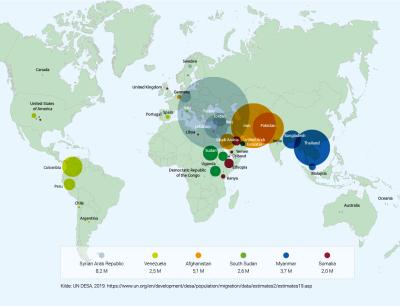

Six largest diasporas from conflict-affected areas and major countries of residence

Blurred boundaries between development and humanitarianism

The difficulty of clearly compartmentalising the role of diaspora groups in the humanitarian space reflects both the multi-faceted ways in which they are tied to their erstwhile homelands, and the fact that they are often actively involved before, during and after emergencies. Their mandate is not governed by legally binding and ratified agreements. They are, to a large extent, guided by family ties and a sense of moral and religious obligations. As such, these groups tend to fill the gap between immediate, acute relief and longer-term development. Indeed, they reveal that the distinction between relief and development is mostly a reflection of institutional labelling practices. Remittances are a case in point. They may be provided during humanitarian crises, but not exclusively so, and surpass humanitarian aid by six times in conflict-affected countries.

Assistance builds on social networks

Diaspora groups connect sites and actors across geographical distance, either through close-knit, pre-established social networks or via readily mobilisable ones. Diaspora assistance intertwines with, and draws strength from, existing relations with structures of authority in the contexts of delivery. This position enables rapid mobilisation and delivery, because information is easily communicated, needs are informally assessed, and distribution, for the most part, takes place locally rather than regionally or nationally. These characteristics are key strengths, yet conversely, also potential weaknesses. A considerable degree of trust is built into diaspora humanitarianism from the outset, facilitating engagement across the scale. Yet, while remittances and other types of support might flow speedily and reach places that targeted aid may not, they do not necessarily reach those most in need if they lack social capital and access to resourceful networks.

Informal accountability and absence of overall coordination

The affective and socially embedded nature of diaspora support suggests several ambivalences. Precisely how resources are being used is difficult to ascertain; they could be divested into neo-patrimonial networks, political or even conflict-related activities, regardless of original intentions. Even with acts of genuine altruism, humanitarian engagement must account for existing power relations, and therefore some level of protection and enhancement of self- interest may be inevitable.

Furthermore, diaspora humanitarian actors are usually not embedded in formal frameworks that structure their engagement, help or even seek to improve coordination with the official humanitarian system. Accountability tends to be informal and trust-based, structured around reputation and social sanctions. Consequently, paper trails and bureaucratic checks and balances are limited, while response times are cut when diaspora actors can bypass time-consuming application, delivery, and reporting procedures. However, it is also one of the reasons why humanitarian organisations often distrust them.

At the forefront of socio-technical systems of assistance

Diaspora actors are notable innovators in the development of infrastructures when mobilising and channeling assistance and, generally, in staying connected to the homeland. An example is remittances – or cash transfers in humanitarian lingo – that are an important aid modality. Online communication platforms, such as WhatsApp, Facebook and Twitter have also become pertinent. In the Somali case, closed WhatsApp groups, based on kinship or local ties, have become virtual hubs for mobilisation and accountability, through the sharing of photos and other forms of evidence of assistance. GoFundMe platforms are also popular, especially amongst younger users. Global and public mobilisation may reach a group of contributors outside existing social networks, but they risk alienating people whose trust in diaspora support is based on social and affective relationships.

A need for more in-depth knowledge

There is ample evidence that diaspora humanitarianism grows out of existing social networks, but there is a dearth of in-depth research on the roles of diaspora actors and the implications of their engagement with respect to:

1. Local actors and crisis-affected local populations, particularly concerning how diaspora support affects the target populations across ethnic, social, gender, economic and political divides.

2. The relationship between diaspora humanitarian actors and the international humanitarian system in terms of working together, trust, overlaps and friction.

3. The infrastructures used for mobilisation and delivery, not least regarding the role of gender and generation.

4. How power relations intertwine with, and shape, diaspora humanitarianism internationally, nationally, and locally.

The brief is an output from the Diaspora Humanitarianism in Complex Crises (D-Hum) research project, focusing on the Somali regions. It is funded by the Danish Consultative Research Committee (FFU).